𝐖𝐡𝐢𝐭𝐞 𝐌𝐚𝐧’𝐬 𝐁𝐮𝐫𝐝𝐞𝐧 𝐑𝐞𝐝𝐮𝐱: 𝐓𝐡𝐞 𝐈𝐂𝐂’𝐬 𝐒𝐡𝐨𝐰 𝐓𝐫𝐢𝐚𝐥 𝐨𝐟 𝐃𝐮𝐭𝐞𝐫𝐭𝐞

What we will witness in The Hague is a foreign-imposed historical revision. Duterte will be painted as an enemy of his own people, of the world, of humanity itself. But as Pierre-Joseph Proudhon once

A show trial—that is what the prosecution of former Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte at the International Criminal Court (ICC) is destined to become. Duterte isn’t in The Hague for ICC prosecutor Karim Khan to prove his guilt beyond a reasonable doubt; his verdict has already been preordained by Western media, international human rights organizations, and foreign governments.

But this trial isn’t just about Duterte—it’s also a prosecution of the millions who elected him and sustained his high approval ratings throughout his presidency. It’s a trial not against one man, but against the 𝘥𝘦𝘮𝘰𝘴 who gave him the mandate to address a problem that had long terrorized their everyday lives. An acquittal for Duterte is unthinkable—it would shatter the ICC’s already crumbling credibility as the court desperately clings to its fading legitimacy. But a conviction would go far beyond condemning Duterte; it would be a brazen dismissal of the will of the Filipino people—a 𝘥𝘦𝘮𝘰𝘴 that chose him. It would amount to the West, once colonizers, arrogantly lecturing a sovereign nation that they were wrong to elect a leader who addressed their most pressing crises. Such a verdict would not only punish Duterte but also undermine the very essence of national self-determination.

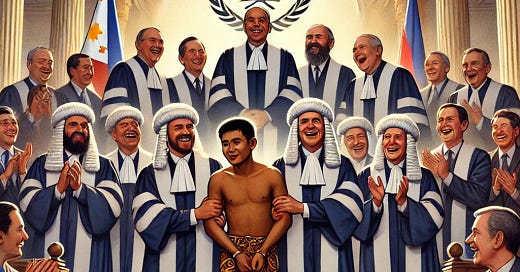

As the court’s first high-profile Asian defendant, Duterte is the ICC’s golden ticket—an opportunity to shed its image as a “colonial white man’s court” fixated on African leaders. Yet, this trial, far from being a pursuit of justice, is a calculated move to rebrand the ICC while reinforcing the very paternalistic dynamics it claims to transcend. It is, in essence, the White Man’s Burden reimagined—a 21st-century performance of an age-old script, where the West assumes the role of moral arbiter, dictating how the Global South should govern itself.

English poet Rudyard Kipling wrote The White Man’s Burden in 1899, urging the United States to colonize the Philippines after assisting Filipino revolutionaries in their war of liberation against Spain. Kipling’s poem framed imperial conquest as a benevolent duty—an obligation for the West to “civilize” and discipline the so-called lesser races. The echoes of colonial moralism are unmistakable in Duterte’s case. Duterte is ICC’s “half devil and half child” in Kipling’s poem. He is paraded as a trophy kill—a prize for the ICC to flaunt, proving that it can extend its reach beyond Africa.

ICC presents itself as a neutral arbiter of justice; but reality doesn’t agree. No Western leader has ever stood trial at The Hague for crimes they have committed. Take, for example, former British Prime Minister Tony Blair and Foreign Secretary Jack Straw, who spearheaded the 2003 invasion of Iraq—a war widely-condemned as illegal and based on false pretenses. In 2016, former Iraqi General Abdul-Wahid Shannan ar-Ribat sued Blair and Straw in a British court, accusing them of committing the crime of aggression.

Yet, in 2017, the London High Court dismissed the case on technicalities: the crime of aggression was not recognized under English law, Blair and Straw had immunity at the time of the alleged crime, and ar-Ribat lacked approval from the sitting UK Attorney General. The ruling ensured that the architects of one of the most destructive modern wars—a conflict that resulted in hundreds of thousands of deaths—escaped accountability.

What did the ICC do? Nothing.

This stark contrast underscores the real nature of ICC prosecutions. Leaders from weaker nations—often those who defy Western influence—are pursued aggressively, while those from powerful states enjoy institutionalized impunity in the ICC.

After Duterte’s arrest, ICC prosecutor Karim Khan, a British national, triumphantly announced the good feedback they received. “It is important for the victims,” he declared. Yet, the victims of his own country’s crimes—Britain’s illegal invasion of Iraq, which resulted in the deaths of hundreds of thousands of civilians—seem to hold no such importance. Despite their responsibility, neither Tony Blair, Jack Straw, nor any British soldier has been dragged from their homeland and paraded before the world as a trophy-kill, unlike Duterte. His arrest warrant cites 43 deaths over an eight-year period—a stark contrast to the inflated figures of 6,000 to 30,000 peddled by Western media and NGOs. This number pales in comparison to the staggering toll of Blair’s decade-long war in another country. Yet, Blair remains free, pocketing six-figure sums for speaking engagements before audiences who likely revile Duterte. The preaching does not match the deed.

The British people never voted for Blair to invade Iraq, topple its leader, and destabilize an entire region. Duterte, on the other hand, was elected on the promise of a hardline approach to drugs—and he delivered. Throughout his presidency, his approval ratings remained high, even as Western critics condemned his methods. According to Social Weather Stations (SWS), Duterte left office with a net satisfaction rating of +81—the highest exit rating of any Philippine president since 1986. Blair, by contrast, was despised when he left office. According to an Ipsos poll, Blair had an abysmal 31% satisfaction rating, with 60% dissatisfied, leaving him with a net approval of -29—a staggering contrast to Duterte’s +81.

But Duterte’s popularity was not just about approval ratings. Filipinos felt safer under his leadership. In June 2016, before Duterte took office, fear of drug addicts roaming Philippine streets was very high. According to SWS, 82% of Luzon residents feared drug addicts in their neighborhoods; 64% in Balance Luzon; 60% in Visayas; 46% in Mindanao. Duterte left office with these numbers plummeting to an all-time low: 48% in Luzon; 36% in Balance Luzon; 28% in Visayas; and 34% in Mindanao. This is a fact his critics conveniently ignore. How many British citizens felt safer after Blair’s invasion of Iraq?

But isn’t this trivializing the victims? Some may ask.

The victims—the lives lost in the war on drugs. The collateral damage. The innocent.

Ah yes, the victims—who suddenly matter enough that their suffering justifies whisking a former president away from his own country to face foreign judges who couldn’t pronounce his name right, rather than his own nation’s courts.

But why is it that the families destroyed by drugs—the parents who lost children to addiction, the innocent victims of drug-fueled crimes—aren’t considered victims by the so-called international community? Why is a drug pusher peddling meth to teenagers immediately excused as a victim of poverty, yet a drug pusher killed in a police operation is a victim worthy of the world’s tears? Why do the victims of heinous crimes committed by crystal meth addicts in the Philippines never enter the discussion? Where’s the global outcry for them? None. Is it because they are not victims of state policy?

But isn’t allowing illegal drugs to run rampant also a state policy—a policy of neglect, complacency, or indifference? When a government fails to protect its people from the dangers of illegal drugs, does it not bear responsibility for those who suffer because of that failure? Or does international accountability only become relevant when collateral damage piles up, after drug pushers perish, drug addicts die, after a government finally takes the problem seriously—when it dares to launch a war against drug syndicates instead of letting them flourish unchecked?

There are no wars without casualties. No wars without belligerents. Yet, in Duterte’s war on drugs, he is conveniently portrayed as the sole belligerent. What happened to the real cause of the war—the drug syndicates? They are conspicuously absent from the global narrative. His conviction will send a chilling message to current and future leaders of the Global South: dismantling drug operations, which requires more than just a nod to the rule of law, could lead to their downfall, just like Duterte.

Europe knows how difficult it is to confront drug syndicates terrorizing their societies—a fact they conveniently hide behind the fig leaf of their liberal approach to drug use. In 2023, Europol’s head Catherine de Bolle admitted: “What is really worrying to us is the increase in violence. Not only regular violence: contract killings, torture, explosions, really tough and hard violence with a lot of dead people.” So why is it that when Europe grapples with its drug problem, the syndicates are rightly seen as the enemy, yet in the Philippines, they are barely mentioned by Western media? Shouldn’t European governments be held internationally accountable for allowing drug syndicates to unleash terror in their societies, making their streets unsafe? Instead, it is Duterte who must be condemned by the world—a glaring double standard that exposes the performative moral indignation of the so-called international community.

Duterte is now 80 years old. Given how long ICC trials last, he may never set foot alive on Philippine soil again. The gravity of this fate is lost on ICC officials who think only of preserving their careers, their fading institution, and the positive press from this spectacle. Why, then, can’t Duterte be tried by Philippine courts, especially under a government led by his political adversaries, who wield significant power? The answer is as simple as it is cynical: the stars have aligned for the ICC and Duterte’s foes. His political enemies seek to exile him from the Philippines, while the ICC, desperate for a high-profile conviction, sees him as the perfect trophy-kill to restore its waning relevance.

What we will witness in The Hague is a foreign-imposed historical revision. Duterte will be painted as an enemy of his own people, of the world, of humanity itself. But as Pierre-Joseph Proudhon once said: Whoever invokes humanity wants to cheat.

But let this be clear: Duterte’s true legacy will not be dictated by foreign courtrooms or the Western elite. It will be written by the lived experiences of ordinary Filipinos—by the families who, for the first time in years, found relative peace in their neighborhoods during his presidency, and by those who saw in his leadership a defiant challenge to the entrenched powers that have long stifled the Filipino nation. His story will not be told through the biased lens of international prosecutors but will live on in the hearts of the common Filipino people. In that history, the ICC will be remembered much like the former colonial masters who sought to tarnish the reputation of Filipino heroes, distorting their image to discourage others from following their path of resistance. Duterte’s legacy, like theirs, will endure not as a cautionary tale but as a testament to the courage of those who dared to fight for their people.

When time has dulled the sharp edges of passion and prejudice, when the light of reason finally pierces through the shadows of misrepresentation, historical justice—its arc long but bending inevitably toward redemption—will demand a reckoning. It will compel a re-evaluation of what was hastily condemned and what was imprudently celebrated. In that clearer light, the truths obscured by the noise of the present will emerge, giving way to who Duterte really is to the 𝘥𝘦𝘮𝘰𝘴 who elected him: Hero.

I agree with what Professor Van Ybiernas mentioned. Duterte is a nationalist and he knew the fate of Rizal and Bonifacio. Both sacrificed their lives to fight for the country against the colonizers. Duterte knows his life would be a sacrifice as well. And he accepted his fate in a calm manner. With all the chaos during the arrest RODRIGO Duterte was calm. Just like the other Filipino heroes who were betrayed by fellow Filipinos, the oligarchs, the rich, Duterte also was betrayed by the Oligarchs. As Van Ybiernas said, in our history, the Oligarchs or the rich people do not want the person who is loved by the People, the masses.Duterte is loved by the masses. That is why he was betrayed by the Filipino oligarchs, the rich. Duterte may come back dead or alive. Whatever happens, he is a true Filipino hero

Duterte was not only instrumental in reducing the proliferation of drugs, he was also able to forge peace brought about by the Muslim rebellion and weaken the communist insurgency that has long plagued our nation. Thus, this has spurned economic development since a big portion of expenses from the above result was used for this. The annual saving from these above activities is now being stolen by corrupt government officials led by congress and bureaucrats in the marcos administration, how sad indeed, that we are cursed by leaders such as these.